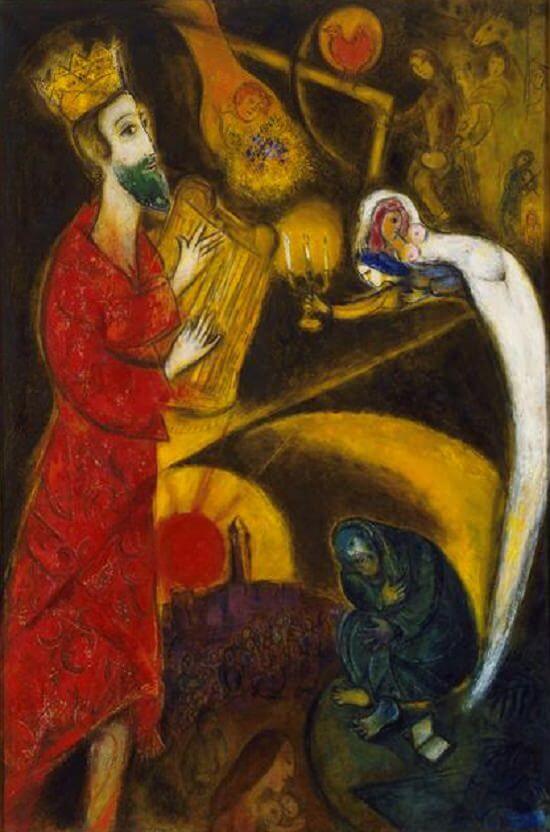

You probably know King David by his unlikely victory over the giant Goliath, with a carefully placed stone right between the eyes. What you probably didn’t know is that it has long been thought that he suffered from depression.

The Psalms, a book of Hebrew hymns, many of which are said to have been written by David, provide a number of clues.

Take for example psalm 31:

Have mercy upon me, O Lord , for I am in trouble :

and mine eye is consumed for very heaviness;

yea, my soul and my body.

For my life is waxen old with heaviness :

and my years with mourning.

Then there’s psalm 69:

Save me, O God : for the waters are come in, even unto my soul.

I stick fast in the deep mire, where no ground is :

I am come into deep waters, so that the floods run over me.

I am weary of crying; my throat is dry :

my sight faileth me for waiting so long upon my God.

Medical doctors have even written journal articles exploring the different mental health conditions from which he may have suffered.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, poet Walter de la Mare imagined King David, in his poem of the same title, trying to alleviate his suffering by summoning a hundred harps to play away the pain. They could not, so he took a stroll in the garden, where he heard the song of a nightingale, whose song seemed to resonate with his experience. King David listened to the singing until all his sadness was gone.

De la Mare’s friend Herbert Howells, one of the greatest composers of the twentieth century, set the poem to music in 1919 and for my money, it is one of Howells’ finest works.

A pupil of some of the finest late-Romantic composers, Howell’s musical language has all the hallmarks of his teachers but seems to anticipate the coming musical trends. Howell’s style is difficult to define, but some features include dense chords and complicated interlocking melodies. The musical biographer Christopher Palmer described Howells’ music like this:

‘…the lines indeterminate and soft-drawn, the sum-total of texture a complex seen mistily through a haze of water or light…effortless interweaving of myriad coloured strands, fluid, self-generating, kaleidoscopic…’

The setting of King David has lots of beautiful elements which are worth our attention.

The piece begins by laying down long, heavy, melancholic chords, which set the scene for the description of King David’s sorrow. As the words begin to describe the music of the harps, Howells introduces exhilarating, broken chords and a soaring melody played in octaves, to mimic their sound. Then, he returns to the opening minor theme as we discover that the harps failed to charm away King David’s sorrow. At this point, the piece takes its most important turn from the key of E flat minor, rising to E major, as David makes his way into the garden. Just as with the harps, Howells mimics the song of the nightingale with a recurring phrase and all the while, King David asks the bird how it came to know his grief. The piece builds to a huge crescendo, with David and the bird not so much in conversation, but in competition. As his sorrow lifts, we return to the original theme of long chords, but now in E major, resolving the mournful beginning, with one last trill from the nightingale.

It is one of the finest marriages of words and music I have ever heard.

But what might it have to teach us?

I was particularly struck by how the nightingale ‘jargoned on and on’, completely oblivious to King David’s sorrow, and yet it was the bird’s song which sang his pain away.

I wonder if you have ever felt a deep sadness which you thought all your own, which you thought no one could ever understand, and then someone said something, maybe just in passing, which put into words precisely how you were feeling and suddenly you felt understood; didn’t feel alone in your pain anymore.

When I became a School Chaplain many years ago, I was told by someone much wiser than me: ‘Craig, your words will sow seeds, the fruits of which you may never see, but they will bear fruit, so choose your words carefully.’ I don’t always get it right, by any stretch of the imagination, but I try always to remember this piece of advice.

I was reminded of the importance of this just a few weeks ago when I travelled to Yorkshire to present a dear friend to her new parishes. After the service, the Bishop came over to me and said, ‘You don’t remember me, do you?’ I confessed that I didn’t. She made me sweat a little, giving me the odd clue as to where we might have crossed paths, until she put me out of my misery. We had sat next to each other at a dinner in London some five years ago and apparently I had said something which has stayed with her ever since. At this point I was thinking, ‘Oh please God don’t let me have said something stupid or offensive.’ Thankfully not. It seems that I had given a passionate theological defence of my sisters occupying the highest offices in the Church. She said that she had never felt so affirmed. I left that encounter both moved that I had said something that had such an impact and terrified that I didn’t remember the encounter.

So, the advice I received as I began my ministry as a School Chaplain turned out to be essential and it seems that I’m still learning. It’s good advice for all of us, not just for School Chaplains.

We spend much of our day speaking to people in all sorts of contexts often without thinking too much about it, after all, we’re busy people. Yet, it might be something that we say which makes all the difference to someone, for good or bad. So, my invitation to you is to be more mindful about the words you use, and rather than jargoning on and on, striving to choose words which build up rather than break down, to heal rather than to wound because it might be your words which ease someone’s sorrow.

I’ll leave you with some more poetry, not from Walter de la Mare, but from the Book of Proverbs, in the Old Testament:

Pleasant words are like a honeycomb,

sweetness to the soul and health to the body.